The hope-based reading list

Read the books that inspired hope-based communication

People have asked me for a list of the books that inform the thinking behind hope-based communication.

So here they are, starting with the non-fiction books that directly inspired the hope-based approach, followed by important works of fiction that shaped my own personal mindset and worldview.

Non-fiction books that inspired hope-based communication

Martha Nussbaum - Monarchy of Fear

This is a wonderful, inspiring work of political philosophy about the impact of emotions on our politics and society. In the aftermath of Trump’s election, Nussbaum writes about the damage fear does to political institutions and the power of hope. It is also a manifesto for a practical hope-based politics to counter fear:

“Hope swells outward, fear shrinks back.”

Hope, she says, is a choice and a practical habit. She also sheds light on why we sometimes avoid hope, because it involves vulnerability and unpredictability about the future, whereas fear offers a certain self-protective certainty. Above all, movements need to embrace hope to bring people out of isolation and into community around a set of goals. If you want more Nussbaum, I also recommend Political Emotions: Why Loves Matters for Justice.

Rutger Bregman - Utopia for Realists & Humankind

Rutger Bregman puts forward bold, radical ideas with a confidence, clearness, determination and passion that gave me the courage I needed to start talking about hope in the human rights space.

Utopia for Realists led me on my first steps to seeing the need to offer solutions, not just problems. We are always reaching for new horizons. Having utopia is about working towards something. The problem today is not that we don’t have it good, its that we dont have an idea of where to go next. Another important point he makes is that what you assume in other people is what you get out of them. We have designed institutions around idea people are selfish. And perhaps also our activism.

He urges us to shift from always talking about problems to making people believe in possibilities and alternatives. We can do this with humility and a sense of humour, using utopias to “Fling open the windows of our minds”.

He also takes progressives to task for being solely “anti” their opponents and “always accepting the premise on which the debate takes place”.

“Anti-privatization, anti-establishment, anti-austerity. Given everything that they’re against, one is left to wonder, what are underdog socialists actually for?”

Pushing, for example, an ambitious policy of Universal Basic Income, he says that “the story of the left ought to be a narrative of hope and progress.”

Humankind is the book that made me realize human rights should be as much about the “human” part as it is about the “rights”. That underlying divides like right/left are deeper meta-narrative struggles, namely, is human nature fundamentally kind and caring, or cruel and selfish? Fascinating in this book is seeing how so much science is driven by our pre-existing answers to these questions: so much evidence for the latter worldview was produced by people who already believed that, and wanted to prove it.

Rutger Bregman reminds us of the goodness of human nature and warns us that pessimism is a self-fulfilling prophecy:

If you look at empirical evidence then you find that assuming the best in other people gets you the best results.”

Kathryn Sikkink - Evidence for Hope

Reading this book was my first “aha” moment about hope. I can trace the moment hope-based communication started to form as an idea from reading the introduction, where Sikkink tells us that having hope is essential for actually achieving change.

It was in that moment that I realised that, though people on the frontline may not always see it, history shows us that even in the very darkest moments a glimmer of hope remains. It occurred to me that what people who feel despair need from human rights groups was not more information about the despair, but hope: some courage and belief that things can get better again.

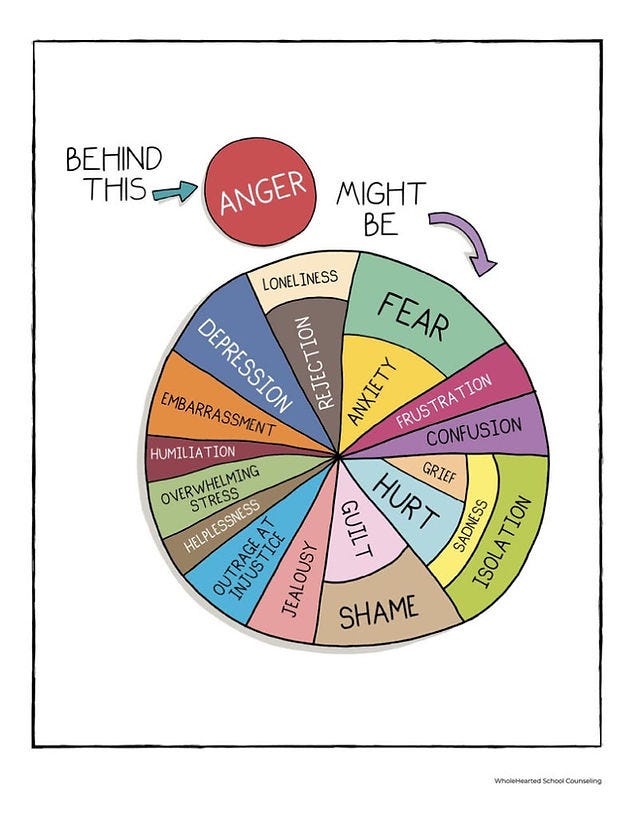

“Anger is not sufficient to maintain motivation over time; you also need to have hope and to believe that you can make difference. In order to know that you can make a difference, you need to have and celebrate small victories that will sustain the work for larger ones.” - Kathryn Sikkink

Sikkink deconstructs some false narratives about human rights: showing that it is an effective movement, but we tend to focus on recent failures instead of long-term success; that it has historically been a grass-roots, global south driven idea, but we allow the narrative to spread that it is elitist/colonialist.

Brené Brown - Atlas of the Heart

Honestly, Brené Brown should be required reading for anyone trying to improve the way human brings treat each other. As with much of the neuroscience and psychology here, I was astounded to read her work and realize that in two decades of studying and practising human rights, these ideas (for example about what happens in the brains of people who we activists “name and shame”) had never been put in front of me.

As Brené Brown writes in Atlas of the Heart, when we feel shame, our brain’s fear response go into overdrive. When anger drives our communications, we risk two things that prevent change: alienating the people instead of encouraging them to take accountability. Second, it can distract us from our own goals and values.

I love how she defines emotions based on practice, defusing, for example, academic battles over empathy. This definition of compassion is perfection:

“Compassion is the daily practice of recognizing and accepting our shared humanity so that we treat ourselves and others with loving-kindness, and we take action in the face of suffering.” - Brené Brown

George Lakoff - Don’t Think of an Elephant & The Political Mind

It never ceases to amaze me that there are people working in politics who have not read these books.

“Behind every progressive policy lies a single moral value: empathy, together with the responsibility and strength to act on empathy.” - George Lakoff

Anat Shenker-Osorio - Don’t Buy It: The Trouble with Talking Nonsense about the Economy

Anyone who knows hope-based knows Anat and her role in inspiring it. This book is such a great introduction to her work and thinking: showing how the way we talk about the economy undermines our efforts to change it. For example, when we personalise “the economy” as something “we need to take care of” it primes us for neoliberal thinking at the expense of caring for actual beings. For too long, our efforts to improve the world have focused on utilitarian efforts to make the case for short-term policies, ignoring the bigger, often harder challenge of how we think about the world.

“If we want people to follow us, it makes sense to describe the place we’d like them to go. Even if that’s the moon and there are no available rockets, it’s important to name the destination if we’re hoping to get people to go along for the ride.” - Anat Shenker-Osorio

Judson Brewer - Unwinding Anxiety & Dzogchen Ponlop Rinpoche - Rebel Buddha

This is a placeholder for all the buddhist writing that shaped my thinking from a young age (my father has practised Tibetan Buddhism for thirty years of so). First of all, the basics teachings around human compassion, about our limited ability to understand the world around us and how our perceptions mislead us.

It has also been fascinating to the confluence of brain science and lessons from buddhism, best represented by Judson Brewer. The more we know about the brain, the more it seems to validate the power of mindfulness and the extent to which our [mis]perceptions are responsible for our [mis]behavior and suffering.

In another book, The Craving Mind, Brewer shows how our brain’s reward-based learning leads to subjective bias. Brewer talks about how addiction works in our brains, but these mechanisms also help explain our brain on politics - how reward systems influence our engagement with political communication and how it can reinforce bias towards other people and groups.

“Simply put, the more that a behaviour is repeated, the more we learn to see the world a certain way. Through a lens that is biased. Based on rewards and punishments from previous actions. We form a habit of sorts the lens being a habitual way of seeing.” - Judson Brewer.

David McRaney - How minds change & Ezra Klein - Why we’re polarized & Anand Giridharadas - The Persuaders

Great introductions to motivated reasoning and identity-protective cognition. Read more about these books here.

What if the best way to change someone’s mind was not by making a great argument, but by saying nothing, and listening to the other person instead?

In How Minds Change, David McRaney explains that deep canvassing reaches people by changing how they think, rather than what they think. It is essential reading for understanding how our biology impacts our politics. For example, our brains are prediction engines that hate uncertainty, but also, over time our brains can internalize new experiences and recognize new patterns. This helps us understand where politics is going wrong, but also see that change is very much possible.

I emerge from this reading with renewed compassion for, and faith in, humanity.

Roman Krznaric - Empathy: Why It Matters, And How To Get It

Empathy is a muscle that he can train and harness for good. Writing about people from the British countryside welcoming refugees from British cities fleeing the Blitz, I was convinced that we CAN make the case for more welcoming societies today. It’s not about resources, it’s about attitudes and empathy. It’s about the barriers we put up to NOT KNOW so that we don’t have to engage with it. The internet age forces us to put up emotional armour to protect from compassion fatigue. Which leads us to….

Lisa Feldman Barrett - Seven and a half lessons about the Brain

Your understanding of the human brain, and how humans tick, will be completely changed by this book. Our brain is constantly trying to make predictions - to make sense of the world - it is a “predicting organ”. What you see is influenced by how you feel.

She says the primary goal of our brain is budgeting our energy use: which helps explain compassion fatigue - we cannot afford the energy needed to “feel the pain” of a world full of suffering. It’s not about “more urgency” in our activism: it is just not physically and biologically possible for our brains to process it.

Lisa Feldman Barrett would prefer we do away with simplistic ideas like slow/fast, upstairs/downstairs ways of understanding the brain altogether. She says they reinforce the old idea of rational/emotional ways of thinking and acting, and draw on outdated metaphors to understand the very complex things at work in our brains. She prefers to talk about our brain functioning as a network of neurons connected by synapses and fluids. These neurons are spread throughout our brain and can carry out all manner of tasks (upstairs and downstairs). What matters is the connections they form with each other.

“It’s impossible to change your past, but right now, with some effort, you can change how your brain will predict in the future. You can invest a little time and energy to learn new ideas. You can curate new experiences. You can try new activities. Everything you learn today seeds your brain to predict differently tomorrow.”

So when we seek to expose, to shame or to punish, we have gotten to the scene of the crime too late. From the point of view of brain science, in the long-term pursuit of justice, neither “preventing” nor “punishing” are as effective as seeding alternative ways of behaving - the ones the society we want to see are built on.

This is why it can be so costly to be ambiguous about what we actually want. When we only focus on the things we fear - climate crisis, the decline of democracy - or call out things we oppose - anti-racism, decolonising, ending austerity, stopping hate - we are only giving the brain more of the same.

We have to be very clear about what we want people to do instead and work on seeding and training those ideas in our brains - through action and through culture.

Our brains learn from our experience, so if we have no experience of that society, we cannot act in accordance with it. All the literature advising us on our personal lives, our habits and our traumas, warns that purely dwelling on the thing we want to change or process - agonising over our inability to stop smoking or snacking, for example - risks reinforcing it. Instead, we are advised to form new, positive habits.

That is why hope as imagining something different and acting towards it is so important. The process is more important than the outcome, because acting starts to bring the hoped-for outcome to life.

Rolf Dobelli - The Art of Thinking Clearly

Grateful to Amanda Alampi for bringing this to my attention - a short, pithy guide to all the bias involved in our thinking and decision-making. You could see it as explaining how limited our conscious thinking is, or how human.

Emma Southon - A History of the Roman Empire in 21 Women

This book is here as a placeholder for all the history (especially postcolonial theory) that taught me to always question my sources of information. Southon is so good at interrogating the very few sources upon which so many stories of Ancient Rome are based - ie a few very old misogynist men. It’s also just brilliant, funny irreverent writing yet deeply learned and wise at the same time.

Gayatri Spivak - Can the Subaltern Speak?

Quick shoutout to the post-colonial theory I read in university which, I realize twenty years later, is actually all about narrative power! See also the Subaltern Studies Reader 1986-1995 edited by Ranajit Guha.

Hopey, changey stuff: Novels that inspire hope and humanity

(noting that hope for us is about finding hope in dark times).

And here are some of the novels that most influenced my general worldview, whether by making me determined to work for human rights, reinforcing my passionate belief in shared humanity as my no.1 value or simply giving me faith that activism and solidarity are worth dedicating my life to.

A lot of these come from the blog about world literature I used to write (and occasionally post to instagram) but have sorely neglected since I started doing all the hopey, changey stuff and was too busy reading all the neuroscience above.

Zadie Smith - NW

This is a book about social mobility, the story of change that occurs between generations of people on the move. The small trials involved in changing society and building better lives. And these things are, for me, ultimately, what all this social change work is about. It's about three interweaving lives in the north west part of London but it is about so much more. It is three young people trying to live their lives and find their way in the world. What Zadie Smith does so well is find the greater significance of small every day moments. In telling the story of a woman of colour who works hard to climb up in the law profession, we feel the toll of the micro aggressions and the just constant effort to change oneself to fit in among the higher class. Natalie succeeds in climbing the social ladder materially but feels the impact in other ways.

Vasily Grossman - Life & Fate

I actually think this is the most important book of the 20th century, a towering novel akin to War and Peace in its broad tapestry of human drama in the midst of brutality and war, but for me far more human and compelling. It is about finding hope in the darkest of times.

And the writer himself grapples with whether to hope. The hero receives a letter from his mother sent from a ghetto about to be liquidated, mirroring his own experience.

He has the reader take the hand of a small boy on that most terrible of journeys, on the crowded train carriage, through the camp and into the gas chamber. What could one possibly write after a chapter like that? Grossman’s answer is to take us back to Ukraine, and tells the story of a soldier from Moscow starving to death. A Ukrainian peasant woman takes him in and nurtures him back to life, even though she is reminded of the men who killed her husband. The message is clear, even in the darkest moments of history, we are salvaged by small acts of humanity.

Grossman was with the Red Army as it liberated the Death Camps, and his essay The Hell of Treblinka and the uprising in which the people imprisoned there burnt that evil place to the ground is one of the most important and gripping pieces of writing in human history. There can be few darker places in human history than Treblinka, a place built solely for mass extermination of human beings. And yet, even amidst that hell, people still found the hope to rise up. This is what I remind myself in dark moments.

Samuel Selvon - The Lonely Londoners & Guy Gunaratne - In Our Mad and Furious City

The ultimate novel of the migration experience. For anyone who has ever wandered around a new city on their own, feeling lost and untethered in the world.

Told with humor and pathos: ‘The English allow us migrants the best part of the day, before they have woken up’.

I love that a more recent novelist Guy Gunaratne names one of his characters Selvon.

Faïza Guène - Du rêve pour les oufs & Kiffe, kiffe demain & La Discretion

Another story that is outwardly apolitical but deeply imbued with themes multiculturalism, post-migration identity but subtly told through great writing and storytelling. You will want to read all Guène’s books (you’re welcome) but this one is particularly affecting in its yearning, loneliness and belief that there is something better out there somewhere.

Faiza Guene is an essential writer for our times: she describes the modern French experience. The supposedly lay republic, sometimes treating all citizens equally, sometimes failing in that promise. She writes about the most recently arrived French people, coming from the Maghreb, but those stories - of hope, of discrimination, of feeling somehow isolated from all your identities and trapped between old and new - mirror almost exactly the experience of my Polish-Jewish family in France before and after the wars. In a way, Europe never got rid of its racism, it just got rid of its Jews, and it is only now reacquainting itself with real multiculturalism.

Danilo Kis - A Tomb for Boris Davidowicz

I first picked this up because Dawidowicz is my mother’s maiden name. I read it to the end because it is a chilling indictment of Communism, and the potential in any movement for liberty to become repressive. It is similar to, but far vaster in scale and perspective than, Arthur Koestler’s Darkness at Noon, in which we follow one Soviet figure tortured into giving a false confession during the purges. However, Kis expands this story across Europe, telling all manner of stories of idealistic socialists and communists crushed within the cogs of totalitarianism. This will not give you hope necessarily, but will remind you to always question your own certainty and remain open-minded.

Koli Jean Bofane - Congo Inc: Le Testament de Bismark

A vast, panoramic 21st century post-colonial novel about the DRC and its place in the world and world history, told through an array of characters who are all too missing from most other novels and narratives today. Full review here.

Ayanna Lloyd Banwo - When We Were Birds

The most recent addition to that rich Caribbean oeuvre.

One of those books you don’t want to end and put down with a sense of dizziness and great significance that you cannot share or express. It is a beautifully atmospheric, spiritual story of people finding their way in a sometimes cruel, indifferent world. Its a book of love and hope and a great antidote to sometimes overwhelming cynicism of world politics (and world football!).

It leaves you with that hopeful feeling that, while we may be surrounded by a hard world that, if you can just find someone to get through the storm together, then you will be alright.

This novel has that secret sauce that makes me love fiction: being deeply political without ever mentioning politics. The dark legacy of colonialism and slavery is always their looming over the story or rather looming from under it-since death and graveyards are such strong themes.

Maaza Mengiste - Beneath the Lion’s Gaze

People trying to survive revolution. Full review here.

Yvonne Adhiambo Owuor - The Dragonfly Sea

We often see the world through a colonial lense: the west went and colonised the world and then we had globalization. This is a much needed “South-South” story bringing to life the rich trade and interconnection across the Indian Ocean that pre-dated and survives the age of European empire. And also just magical evocative writing.

Anita Desai - The Inheritance of Loss

Jack London - Entire Oeuvre - The People of the Abyss

Although best known for his adventure writing, Jack London has a huge and rich oeuvre and is a powerful, empathetic voice for the down-trodden: whether he is writing about poverty (The People of the Abyss), alcoholism (John Barleycorn), social mobility (Martin Eden) or dictatorship (The Iron Heel). Throughout all these trials, humanity

Ousmane Sembene - Les Bouts de bois de Dieu

An inspiring story of anti-colonial resistance, telling the story of the 1947-48 Dakar-Niger railroad strike, told from the perspective of both the striking workers and their wives supporting them. Ends with one of the best fictional speeches ever written. Sembene is a truly great and under-appreciated storyteller of the 20th century, who tells stories of the subaltern.

Earl Lovelace - Is Just a Movie

My love of post-colonial literature goes back to my student days, when the only way to get your hands on novels that were not from minority population countries was the Heinemann African Writers Series and Caribbean Writers Series. The struggle for liberty and identity inevitably flows through the daily lives of these novels, which denounce colonialism but also do not shy away from exposing the failure, hypocrisy and injustice also present within post-colonial societies. I recommend any novel from either series, but you could start with the oeuvre of Earl Lovelace and with one of his more recent books, Is Just a Movie. The writing moves with a magical ebb and flow, and a subtle but strong undercurrent of determined fury at the quiet injustice of everyday life in an unequal society. If you like this, you will also like Augustown by Kei Miller.

Flann O'Brien - The Third Policeman

The best book to come out of Ireland. Just a very funny, ridiculous satire of postcolonial bureaucratic modern life. Particularly for anyone who is already 50% bicycle.

Albert Camus - The Plague

Can’t leave this one out. A warning about fascism that should ring through the ages.

Antonio Benítez Rojo - Sea of Lentils

The origins of the genocide of the Amerindian people dove-tailed with the beginnings of the British role in - and turbo-charging of - the Atlantic slave trade.

Rosario Castellanos - The Book of Lamentations

More brutal injustice and resistance, this time from Mexico.

Daniel Alarcón - Lost City Radio

You may see the trend here, but here is another inspiring story of resistance.

Elizabeth Gaskell - Mary Barton

One of the few “classics” from I personally enjoyed reading (you will notice very few books from the US/UK/France which tend to dominate the “best literature” canon on this list). Probably because it is about the perspectives of the working-class, particularly of women, during the Industrial Revolution, rather than rich people.

Helon Habila - Waiting for an Angel

Robert Harris - Imperium

If you have made it this far, you have earned something fun: a political thriller for West Wing fans. The life of Cicero told as for the era of New Labour.

Abbas Khider - Die Orangen des Präsidenten

A good one for anyone learning German, Abbas Khider is a German-Iraqi writer who writes from personal experience about life under Saddam Hussein. See also his “Aubergine letters” - both are about ordinary, not particularly heroic people, trying to maintain some humanity under brutal repression. I also like their broad geographical sweep. See also Rafik Schami who also writes in German about Syria.

Tahmima Anam — A Golden Age

Bangladesh’s 1971 War of Independence. Full review here.

Abu Bakr Khaal - African Titanics

Need to include something here about contemporary migration and the mediterranean. This novel is a timely reminder of the need for human stories, not just numbers. Full review here.

Raja Shehadeh - Palestinian Walks

This is non-fiction but so beautifully written that it deserves mention here. This was the first book that introduced an individual Palestinian voice to me and I am deeply grateful for it. A reminder of the power of just listening to individual human voices and trying to understand their experience and perspective.

Richard Rive - 'Buckingham Palace', District Six

Another book about apartheid, told from the ground up as a community are force to leave their homes after their homes are designated “whites only”.

That’s a lot of books! Please let me know if you pick any of these up and what you think of them.

That is a wrap for the first half of 2024 from us at the Center for Hope-based Communication. See you in September. In you haven’t already, please sign up to our waiting list to be involved in our exciting new launch in the autumn.