Let’s start with the exciting news…ahead of World Book Day, we are starting a hope-based book club.

The goal: to elevate books that are important for social change and talk about how activists around the world can put their lessons into action. We are going to start with Why We're Polarized by Ezra Klein, a book that draws on the science of human nature to draw conclusions about US politics, but with insights relevant to all human societies - which is why we want to talk about it.

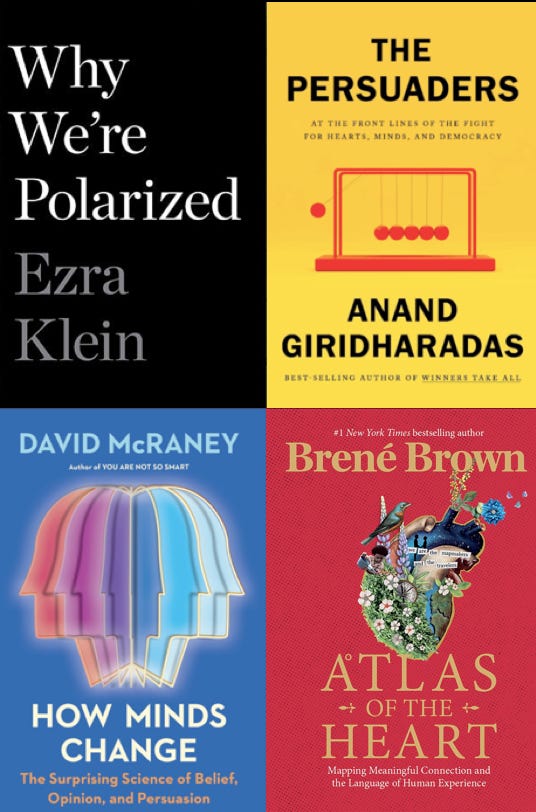

On that note, today I want to highlight four books that I think are absolutely crucial reading for any activist. And don’t miss the links to other hopey-changey stuff at the end.

Sign up here for access to our monthly online meet-ups, and join our hope-based LinkedIn group for ongoing conversations, prompts, and a space to share relevant pieces!

The four books that every activist should read

Does your approach to social justice depend on showing people that they are wrong (and, therefore, that you are right)? Four recent books fundamentally challenge this all-too-common approach, that so many of us are still very much guilty of.

Based on these books, I want to suggest three steps towards learning, accepting, embracing that we, along with all other humans, can be wrong, even (especially) when we feel like we are right.

Step 1: Recognize when our certainty makes us bad communicators.

Step 2: To change minds, listen.

Step 3: Make the conversation (not its subject) the story.

The TL;DR: Our decision-making is a mix of reason and emotion.

There is no reasoning without emotion, nor emotion without reason. The idea of appealing to “hearts and minds” is a false dichotomy - because humans always use both together. Human rights cannot rely on reaching the audience’s mind, we have to reach the heart too. It feels hard to reach other people who seem to think so differently from ourselves, but remembering that they are human too is a universal starting point that should give us all hope that we can all change.

We just have to be willing to change a little ourselves too.

Before you set out to change the world, ask yourself whether you are ready for the world to change you?

Step 1. Recognize the risk of certainty

Our thinking is driven by belonging

Ezra Klein’s book Why We’re Polarized shows why in this digital age, simply providing information (“raising awareness”) is unlikely to create social change:

Humans form groups incredibly quickly — not just based on obvious things like nationality, for anything, sports clubs, as members of teams within organizations, or just being sorted into groups.

For our brains, belonging to our group is a matter of life or death. From an evolutionary perspective, being ejected from your tribe leaves you exposed and vulnerable to danger. Belonging means safety. Which means that even the risk of not belonging triggers our most basic survival instincts: the fight-or-flight response.

When groups have values and political positions, supporting those positions is a matter of belonging to that group identity. Questioning those positions threatens the sense of belonging that is fundamental to our well-being and self-worth.

What does this mean? When we process new information, like political messages or the news, our brain makes it fit our group identity’s worldview, as opposed to objectively evaluating the facts. Information that fits our existing beliefs reinforces that ‘we are (I am) right’. But if when the information challenges those beliefs, we question the information itself (aka confirmation bias).

“The human mind is exquisitely tuned to group affiliation and group difference. It takes almost nothing for us to form a group identity, and once that happens, we naturally assume ourselves in competition with other groups. The deeper our commitment to our group becomes, the more determined we become to make sure our group wins.”

…

“An identity that binds you into a community you care about is costly and painful to abandon, and the mind will go to great lengths to avoid abandoning it.”

-Ezra Klein, Why We’re Polarized

Motivated reasoning - “what you believe is what you see”

The process that results is called motivated reasoning or identity-protective cognition: Klein explains that our thought process is not a neutral actor, it is motivated to defend our group’s position, or whatever conclusion we need to reach to belong or reinforce our identity. In order to maintain that comforting feeling of remaining within the group, we resist facts that threaten our its defining values. To accept those facts triggers our most primordial fear response: because what is more dangerous that being out there in the world on our own?

In other words, while we assume our thinking is pure reasoning, it is often actually more motivated - without us being conscious of it - by protecting our identity from uncomfortable questions.

The most important human psychological imperative is protecting our idea of who we are and our relationships with the people we trust and love — this means that we tend to agree with people around us, even when its wrong!

Why does this matter for human rights and other social change activists?

If your cause is seen as belonging to one political group, people from other groups are likely to reject it. And if your ‘criticism’ singles out a specific group, with the goal that they take responsibility and open their minds to the alternative views you offer, the much more likely reality is that they:

reject the messenger by questioning your motivation (i.e. you),

experience a stronger connection to the criticized group, reinforcing an us-versus-them dynamic,

integrate your criticisms into their identity.

For a long time, causes like human rights relied on reason, reporting and utilitarian logic. But what happens when these same tools are used to justify or obfuscate violations?

Clever people have confirmation bias too

Here’s the thing: THAT GOES FOR YOU TOO! We sometimes talk about confirmation bias as a way to explain why other people support politicians we don’t like. But actually, the more intelligent you are, the better your brain is at identifying patterns - and pattern recognition allows us to make information fit our worldview.

In other words, to understand the perspectives of people you do not already agree with, you have to work extra hard to challenge your assumptions.

The science, from David McRaney’s How Minds Change: our brains are prediction engines that hate uncertainty:

“When the truth is uncertain, our brains resolve that uncertainty without our knowledge by creating the most likely reality they can imagine based on our prior experience […] When we encounter novel information that seems ambiguous, we unknowingly [disambiguate] it based on what we’ve experienced in the past.”

Action: how “identity mindfulness” can make us better human rights communicators

It is harder to operate in the world with less certainty. But knowing how our brain works can help us recognize when our identity might be driving how we think. Ezra Klein’s conclusion calls this identity mindfulness.

So when we feel our heart rate increase, our stomachs turn, when we feel outraged at hypocrisy or other positions we fundamentally disagree with, we can do these things to improve our communication:

Check-in with ourselves — ask what is driving our response. Remember that you are human: you might be feeling particularly intransigent because of motivated reasoning. That feeling of certainty might be less fact-based and more identity-based than you would like to think. Indeed, the more certain you feel, the more likely it is to be just that: a feeling, driven by your very human need for belonging and certainty.

Question whether that motivated response makes our activism efforts less effective, and then ask how we want our audience to feel to achieve our social change goal. Remember that they are human: it might be they reject your facts because of the same physical, chemical and emotional barriers. Their intransigence might not be driven by hate, but by fear. That opens up new avenues for changing their minds…

Step 2. Change minds by listening

Shame is a great way to trigger identity-protection

When we feel our identity being attacked, our self-worth (our source of meaning in life) is challenged.

The result: we get defensive, because being wrong is tantamount to questioning who we are. As Brene Brown writes in Atlas of the Heart, When we add shame to the mix, our brain’s fear response go into overdrive.

When anger drives our communications, we risk two things that prevent change: alienating the people instead of encouraging them to take accountability. Second, it can distract us from our own goals and values:

“Anger is an action emotion - we want to do something when we feel it and when we’re on the receiving end of it. …anger is also a full contact emotion. Because it activates our nervous system and can hijack our thoughts and behaviors, it can take a real toll on our mental health.” - Brené Brown, Atlas of the Heart.

So what do can we activists do instead of naming and shaming?

We can listen!

“When we try to convince people to think again, our first instinct is usually to start talking. Yet the most effective way to help other people to open their minds is often to listen.” - Adam Grant, Think Again

We often think that politics is about making good arguments, and expressing them right. But it is listening that changes minds.

In How Minds Change, David McRaney explains that deep canvassing reaches people by changing how they think, rather than what they think.

When you encourage people to talk through their own thinking processes and draw on their own experiences to relate to those of others, people feel a canvasser cares about them and their opinions. When they see that the canvasser might even ‘be on their side’ (despite their acknowledged political differences), they show more inclination to change their minds. Human rights, a cause dedicated to the rights of all humans, should be able to make anyone feel that we are on their side.

Again, the perception of ‘sides’ or group belonging is more powerful than facts or clever arguments in political opinion formation.

“...reasons, justifications, and explanations for maintaining one’s existing opinion can be endless… Deep canvassers want to avoid that unwinnable fight. To do that, they allow a person’s justifications to remain unchallenged. They nod and listen. The idea is to move forward, make the person feel heard and respected, avoid arguing over a person’s conclusions, and instead work to discover the motivations behind them. To that end, the next step is to evoke a person’s emotional response to the issue.”

-David McRaney , How Minds Change

If we listen to others, are we legitimizing their ideas at the expense of our own?

Listening does not mean shelving your own values: on the contrary. To show people that we really care about our cause, we can frame it as a cause, ideas, we simply want to share — not shame, correct, or confront them with.

What matters to the audience is our intention. Being vulnerable about our values, motivations and vision - we may not achieve our goals, we are not perfect - might make people open to our ideas.

“When someone knowledgeable admits uncertainty, it surprises people, and they end up paying more attention to the substance of the argument.”

-Adam Grant, Think Again

The reality is we need people to be part of our cause in order for that cause to gain the momentum and strength it needs to create change. And so, rather than demanding people value us, we need to show we value them.

People join movements to feel listened to, valued; to belong. When talking about the growth of progressives in the US, Anand Giridharadas explains that to gain support, one should focus less on transactional policies (free internet!) and more on offering meaning and belonging; on calling-in the waking, so that they become woke.

Step 3. Have conversations instead of debates

“Debates have winners and losers, and no one wants to be a loser.”

-David McRaney, How Minds Change

Human rights beyond the information deficit model

Before the internet, human rights communication was built on raising awareness, and naming and shaming perpetrators. Today, we can no longer tell ourselves that the problem is a deficit of information or awareness, but that amidst the constant and endless amounts of information, some (a lot) gets swamped and ignored.

“What the digital information revolution offered wasn’t just more information but more choice of information. […] The digital revolution offered access to unimaginably vast vistas of information, but just as important, it offered access to unimaginably more choice. And that explosion of choice widened that interested-uninterested divide. Greater choices lets the junkies learn more and the disinterested know less.”

-Ezra Klein

If you want to make people consume your information, you have to make them care about consuming it.

The work of exposing violations remains vital, but if we actually want people to care about the lives of those involved, we cannot just put more information out there: we need more sophisticated strategies to make people care about what happens to their fellow human beings. To do this we have to understand what drives interest and engagement - identity. Building identity is a prerequisite for communication in the digital age.

Ezra Klein writes that journalism also reinforces identities - things that appear neutral to us tend to actually just be our our perspective or identity reflected back to us. No human brain is neutral, we can only understand the world based on our own experience, which creates a unique perspective and bias that we bring to everything we say and do.

Similarly, communication is never just a neutral transmission of facts, identity is bound up in both the creation and consumption of content:

“Identity-oriented content will deepen the identities it repeatedly triggers, confirms, or threatens. It will turn interests or opinions into identities.”

Instead of hiding our identity, we should be open about it, and embrace it. It is actually the best tool we have for effective communication.

If communications is not about telling people facts, what is it for?

Social change communications is about presenting people with new ways of thinking AND new ways of behaving. Unless you constantly repeat your values, people’s ‘plastic brains’ won’t integrating them into their ways of thinking.

Ask yourself: once their awareness is ‘raised’, how do I want people to think AND behave differently?

Build your strategy around those changes in attitude and behavior you want to see.

Start showing them those ideas and actions so they can copy them and connect them to the sense of meaning and belonging every human needs.

Identities can evolve, which means minds can change

While our brains interpret new information based on past experience, David McRaney also tells us that over time our brains can internalize new experiences and recognize new patterns. The caveat: “the patterns that never get noticed never become part of that animal’s internal world.”

“Thanks to brain plasticity, through repeated experience, when inputs are regular and repeating, neurons quickly get burned into the reciprocal patterns of activation.”

In other words, you have to show people the new thing you want in an engaging and exciting way. Potentially being wrong, being passionate about a vision you may fail to realize, being clear about the values you stand for - that makes you interesting.

“To put it simply, in a media driven by identity and passion, identitarian candidates who arouse the strongest passions have an advantage. You can arouse that passion through inspiration, as Obama did, or through conflict, as Trump did. What you can’t do is be boring.”

Action: New identities, new narratives

This science underpins the basic principles of narrative strategy: you need to push your own narrative, not counter other people’s. To counter harmful narratives and the identities they prey on, you must offer identities conducive to social justice.

Reduce the power of dominant identities by increasing hope and reduce fear so that people feel more confident stepping beyond their main identity.

Offer new and multiple identities for people to belong to, and through which to understand various issues.

Offer a helpful identity that helps human beings find common ground: one of shared humanity, as spelled out in our Visual Guide for Communicating Human Rights.

Conclusion: a tool for humanity

Before the internet, we needed human rights work to expose violations happening far away. Now that we are overwhelmed by information, and desperately clinging to identity, belonging and meaning, we need human rights as an identity to help us see and hear the voices of other human beings.

The human rights movement can offer the identity that allows that to happen, if we spread narratives that:

Prepare us to reconsider what we see before us, recognizing the limits of our own perception, and recognize the value of others’.

Trigger the basic human values that lie in all of us: kindness, caring, love.

Makes us care about other people and their ideas, simply because they are human.

This is human rights not as telling people we are right, but as a way of living our lives together. A tool for finding what we have in common, but also for accepting what is different.

Hopey, changey stuff

Practical application of this brain science: how human rights activists should talk about international politics. This oped from communications strategist Valeriia Voshchevska argues the need for unifying empathy-based narratives rather than using cynical “what about…” or “double standard” narratives.

It can take just TWO SECONDS for new information to turn into subjective, experience-based memory, suggests brand new neuroscience research featured in the Guardian. Is it just me or is thinking about the brain and our behaviour becoming more mainstream? Time for activism to catch up…

Awe can be a powerful driver of empathy and support for welcoming others, new research based on exposing children to art suggests. More evidence that social change communicators can feel confident leaving behind outrage and fear and engaging a new, hope-based set of emotions.

I think we need to create new initiatives and new brands dedicated to spreading our values. I call this movement communications, inspired by this article about Movement Journalism.

What does movement communications look like? Sneak preview of a new case study from El Salvador, in our forthcoming Narrative Communications Strategy Toolkit.

That’s it for this edition. Don’t forget to join our hope-based book club on LinkedIn and sign up for the first session on Tuesday, 23 May here.