As we navigate the beginning of another Donald Trump administration, many people are struggling to stay hopeful, healthy and motivated - me included! How do I send out a post about hope when things seem so dark?!

I first developed the hope-based communications approach in response to a similar moment in time: Trump's 2016 election win and his first year in office in 2017, which started with that shocking Muslim Ban. Back then, I started developing the hope-based approach in recognition of the urgent need to shift how we communicate for social change. Revisiting some of the core principles of this approach feels especially important now, to help us all find a way forward.

So I’m sharing some of the ideas I shared on a panel last month about balancing hope and pain in human rights narratives in documentary filmmaking. The panel, Filmmaking for Social Justice, was hosted by the upcoming FIFDH human rights forum and film festival in Geneva as part of their Impact Days programme.

Hope is for dark times

Hope-based communication was born in the period around 2016-2017, a time that carried a similar political darkness to what we see today. During that time, I worked in communications for Amnesty International and had a realization: simply showing people suffering human rights violations wasn’t enough to create change.

The news was dominated stories of people fleeing war and persecution, but it wasn’t creating enough compassion and welcoming in our politics.

This led me to explore psychology and brain science to better understand human behavior. As I started learning about the role of emotions in our decision-making, I was shocked that I hadn’t done this sooner.

The science of compassion

In social change work, our goal is to improve how humans treat each other, yet we weren’t using the science that explains what drives empathy and compassion. I realized that my work as a human rights communicator was about fostering compassion - the kind that Brené Brown defines as recognizing our shared humanity so that we genuinely care for others.

The insight that changed everything for me came from neuroscience: all human beings have a fight-or-flight response. When we are in fear mode, our capacity to understand the perspectives of those different from us shuts down. Fear primes us for self-interest.

It’s common sense: if we sense danger, we instinctively take care of ourselves and our group. I realized that much of the urgent, crisis-driven, fear-based communication in human rights work might not be priming people for the response we want. Instead of fostering hope, agency, and empowerment, we may be reinforcing fear and self-preservation.

There is an alternative. Because we humans are also equipped with a tend-and-befriend response. To achieve our social change goals, we need to consider the emotions we evoke in our audiences and in society as a whole.

Anger mobilises, hope organises

One thing we discussed on the Impact Days panel was anger.

Anger, like fear, triggers the same response in the brain. It is often a reaction to a lack of control. In hope-based communication, we say that anger mobilizes - it can provoke short-term action, like attending a protest or signing a petition. But hope organizes. If we want to build lasting movements that transform attitudes, behaviors, and culture (ABC strategy!), we need to organize around a shared goal.

Often, we associate justice with punishment, and anger is closely linked to that. When we see punishment - whether through public shaming or courtroom verdicts - we get a dopamine hit. The same chemical reaction occurs when we see someone from an opposing group being punished. Understanding how our biology shapes our politics can make us not only better activists but also better human beings.

The hope-based approach involves becoming more aware of how our biology might be driving our strategy and, for example, asking ourselves whether we are motivated by a desire to punish or to heal. That might encourage us to balance some of “justice as punishment” approach with more restorative justice.

So how do we create shared humanity? Countering dehumanisation with rehumanization

How do we foster empathy without relying on the existence of an enemy or an outside group? This process is what we call rehumanization, which is essential for storytellers. We must ask ourselves: Are the stories we tell reinforcing dehumanization without us realizing it? More importantly, how can we intentionally tell stories that foster empathy and compassion?

This is what we address in hope-based shift number 5: from victim to human, where we ask ourselves who the protagonists of our story are, and whether their hopes and aspirations are heard, not just their fears and suffering. We find that this allows audiences to relate to people on the level of shared intrinsic values and shared goals, finding a common ground in which genuine solidarity can take root.

The story we tell today is the action we all take tomorrow

A key insight from brain science is that our brains are predictive machines. Much of our behavior is subconscious and habitual, shaped by what we already know. This means our brains are wired to accept what is familiar. In a negative sense, this is why hearing a falsehood multiple times makes it feel true. But it also means we can introduce radical ideas about how the world could be and create change simply by making those ideas familiar.

I think this insight has massive implications for social change: it means we need to shift our focus from what currently is, to showing what could be. From raising awareness to changing awareness. We need to tells stories that not only show that change is possible, but make that change feel familiar and real - so that we can feel it on a sensory level: taste, touch, hear and smell!

This is empowering for changemakers, especially filmmakers and documentarians. In human rights and social change work, we often believe our duty is to expose the worst aspects of humanity. But neuroscience tells us that people learn behaviors and attitudes by observing others.

We must be conscious of how the stories we tell shape behavior and attitudes. If we want to see radical change, we must put forward radical visions of the world we want to create. If we don’t, we ensure they will never happen.

Seeing kindness makes us kinder

For me, this is the big shift in hope-based communication. We encourage activists to base their work on the future they hope to see.

Neuroscience shows us that when we witness kindness, our brain processes it as if someone is being kind to us, which in turn drives us to be kind. This not only restores our faith in humanity but also highlights the role of storytelling in shaping the future. We are not just exposing injustices - we are actively constructing the world we want to live in.

This understanding also helps us navigate the dark times we are in. Today’s political landscape is shaped by forces investing heavily in spreading fear and division. Given that fear is a dominant force in our culture, it’s no surprise that it defines much of our politics. But neuroscience also shows us a path forward: by working together to build a new cultural narrative.

Imagine if we invested as much in creating a social contagion effect for shared humanity? What if we invested as much in nurturing the change we hope to see happen as we do in trying to stop the change we fear?

It’s not enough to raise awareness: we need to change awareness.

We must be intentional about the narratives we want to put forward.

Anyone can use hope-based communication by asking themselves:

What are my values?

What story do I want to tell?

What vision of the world do I want to reinforce?

The way we change narratives is through repetition, making our ideas familiar through consistent messaging.

A shared humanity worldview - changing the story we tell about human nature

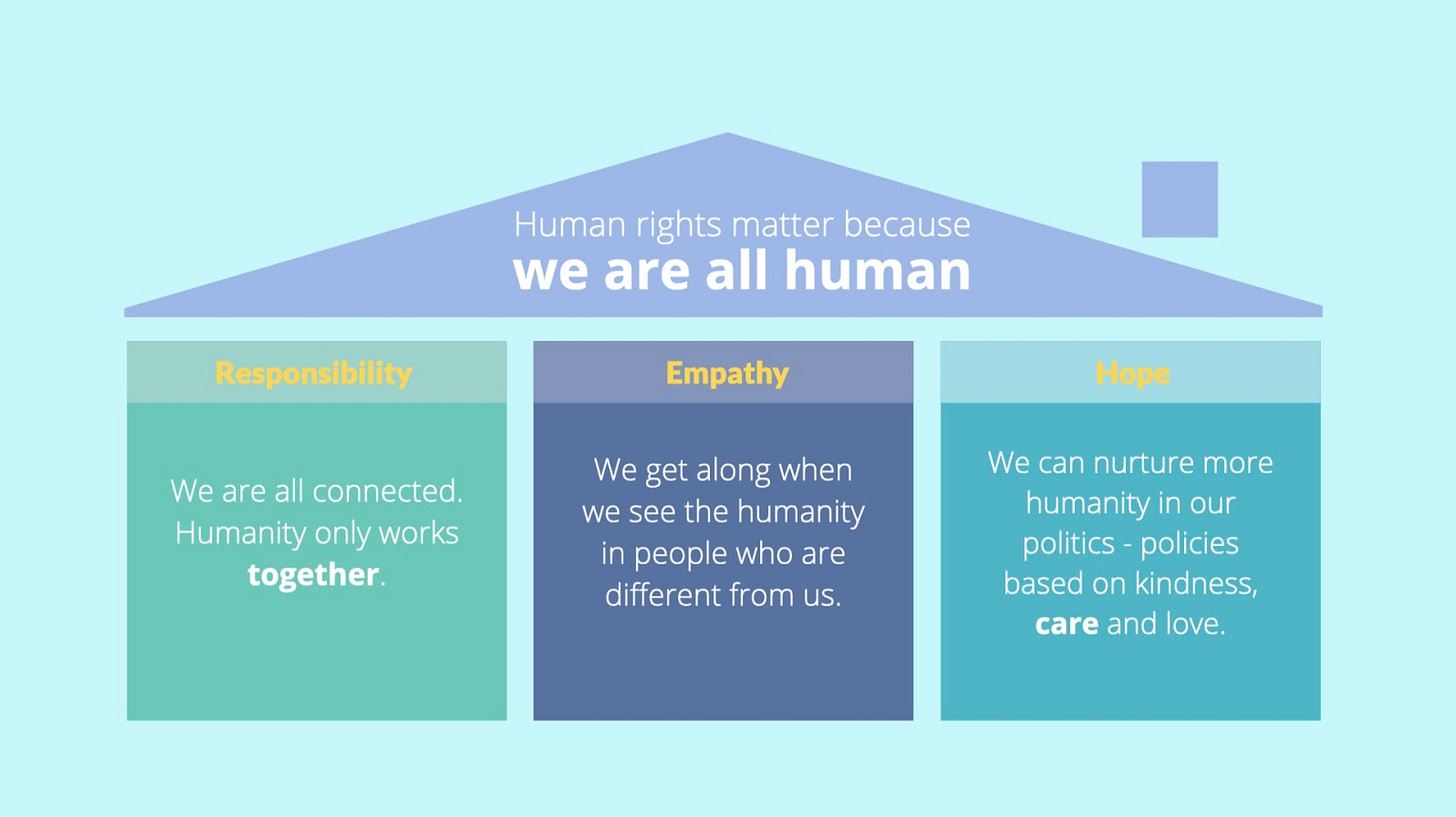

Through workshops with human rights activists worldwide, we’ve identified a core narrative that needs strengthening: shared humanity. On the most basic level, this means reinforcing the idea that we are all human beings and that this identity should shape policymaking. Kindness should be seen as just as rational as cruelty.

In areas like migration, this means shifting from merely documenting suffering to promoting the behaviors we want to see - such as welcoming communities - because seeing these behaviors in action encourages others to replicate them.

Ultimately, this is about reshaping the conversation around human rights.

Are human beings fundamentally good and capable of change, healing, and growth? …Or are we selfish individuals who must be kept in check?

Those who push a dark, divisive vision of humanity are highly organized in using social media to spread their stories. We must be just as strategic and collaborative in telling and amplifying stories that foster empathy, connection, and hope.

Telling these stories is more than communication: it’s a way to rewire our brains and reshape our communities.

Training ourselves to change our perspectives, take on new viewpoints, and practice kindness is possible.

Neuroscience shows us that human brains have plasticity—they are always changing. This means change is always possible. (I just came across a wonderful concept called “self-directed neuroplasticity” which essentially means intentionally changing our neural structure, for example, by training ourselves to adopt new habits.)

What’s next? A new community for people learning how to hope

In five years of developing hope-based communication, I have found it helps activists develop new ideas and strategies, but more than anything, it makes them feel hopeful. Now, we want to see how this approach can be a tool for journalists, filmmakers, and anyone else who wants to use it.

Our next step is to build a community for those who want to explore and develop this approach.

What we’ve learned is that hope is a muscle: it must be exercised consistently.

Adopting a hope-based approach in activism and storytelling is challenging because many organizations, particularly in human rights, are structured to focus on what’s going wrong in the world.

A major issue in social change work is the lack of storytelling capacity. NGOs often see their role as documenting abuses and relying on the media to spread the message. But to truly create change, we need a deeper collaboration between activists and storytellers, particularly filmmakers, so that we can tell these stories strategically and effectively.

In our workshops, activists develop powerful, inspiring visions. Migration advocates recognize the need to tell stories of welcoming communities. Civil society groups facing repression realize they must tell the story of their own resilience. But many lack the capacity to tell these stories and share them widely.

Our goal with this community is to bridge that gap. By connecting activists with storytellers, we can work together on collective storytelling and provide the tools and training needed to use this approach effectively.

We simply want to share this idea with anyone who wants to use it. Because the more we tell these stories, the more we shape the world toward the one we hope to see.

If you're interested in learning more, you can find us on social media or sign up for our waiting list.

Let's start telling the stories that will build the future we hope to see.

Big thanks to Sophie Mulphin and the rest of FIFDH for having me on the panel! You can sign up for their newsletter here.

Hopey, Changey Stuff

I shared the panel with some incredible storytellers:

Egyptian filmmaker Mayye Zayed who presented her documentary Lift Like a Girl

Peacebuilder and producer Adrian Kawaley-Lathan talked about his work as an impact producer trying to focus on showing alternative futures, and of the need to shape a kinder, more compassionate culture in the world.

Juan Mejia showed us a trailer from his new documentary Igualada. It looks AMAZING. It is about the campaign of Francia Márquez, the human rights activist who is now. Vice-President of Colombia. Her story is precisely what we need to remind us that change is possible, if we make it happen. I cannot wait to watch this.

The FIFDH film festival is on in March, worth checking out just for these gorgeous posters!

More hopey, changey stuff

There is a new conference on the scene: I attended Europe’s first Political Tech Summit this weekend. Main takeaway is how progressives primarily use new tech for mobilising supporters to vote, sign petitions and donate, but less for deeper organising such as attitude, behavior and narrative change.

Hope-based expert Fotis Filippou recommends the Ezra Klein podcast episode “Don’t Believe Him”, a reminder of our need to *focus*, not react.

Nice feature on our REWIRE Democracy incubator. Love this quote from one participant, Ágnes Bardócz, about the experience of running her own hope-based training:

“The biggest success, in my opinion, was when one of my former trainers changed her opinion about an upcoming campaign. I witnessed how to rewire someone’s mind, and together we changed the narrative based on the hope-based communications method.

Such an instant success made me feel like I was swimming in happiness, seeing such a result on the spot!”

Quote of the Week

“Hope is a discipline. We should not have a passive relation to hope, but we should be generating and creating hope - that’s the work of activists. We have to believe that a different world is possible.”

Angela Davis, Writer, philosophy teacher & human rights activist present at FIFDH 2024 - thanks to FIFDH for reminding me of this, and using it to start and frame our webinar!

Excellent post.

I've been struggling with how to communicate my message:

Yes, we are facing huge challenges. But we are also present to unprecedented opportunities for creating a better world.

And the magical thing?

The solutions to our biggest, most pressing global problems ARE those very opportunities for building something better.

I'm open to any and all thoughts for how to effectively communicate this.

Thanks!

J.

Loves it ! Thank you